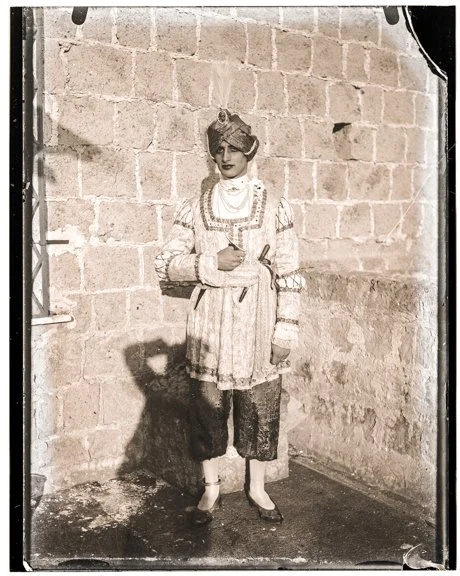

photo © William Kein, 1959.

I am in transit as I write this, on my way to the East Coast for some family time and some much-needed beach time. That doesn’t excuse me from my weekly photo criticism exercise. If anything, I think it will bring an additional degree of insight to this week’s image. This week I will be looking at a photograph by one of the true masters of twentieth century photography, William Klein. As always, if you have any questions or comments, please don’t hesitate to leave a comment at the end of this entry.

A little of the backstory on Klein is appropriate, to start. Though he is American-born, William Klein is best known as a French photographer, having been living in Paris since he was stationed there by the US Army. He attended the Sorbonne in 1948, and though he originally was a painter, it was his filmmaking and photography that brought him great acclaim. His notable photo work ranges from groundbreaking fashion work, particularly his shooting for Vogue in the 1950s, as well as his highly influential book of photographs “New York” from 1954. If there is a style of his that I am most drawn to, it is this work, scenes of street life…frenetic and chaotic, highly contrasted and grainy. Klein has produced a series of books that crucial contributions to the art form, in addition to “New York” he has focused on Paris, Rome, Tokyo, and most notable to this critique, Moscow.

The photograph I’m writing about is a wonderful study in the contrast of emotions, while also being a textbook example of compositional intent. So, what do I see? It is a black and white photograph, with three people fairly-evenly distributed in the frame. It looks as though this photo was taken in the summer, perhaps at a resort, near a lake or a forest, judging by the environment. In the far background is an older, heavy set woman, who looks to be drying off on a park bench. In the middle of the frame, we see an older gentleman, sitting in a beach chair. In the foreground is a young woman, a broad grin on her face, her body slightly hunched over, leaning in towards the photographer. Each person is separated from the others by a strong, vertical element: a pole or a tree. Let’s take a closer look at each of these individuals, and how they relate to each other.

The woman in the far background is looking towards the camera, aware of the photographer, but she is somewhat out of focus, so her expression is a bit hard to judge. However, I believe her presence helps bring additional tension to the photograph. We can then shift our gaze to the older man in the center of the image. He looks as though he might be asleep, or at least dozing off. I wonder if he was at all aware of the photographer. Did he close his eyes and bring his hand to his face as a reaction to Klein’s presence? Is the presence of the young woman affecting him at all? Or, as I said, perhaps he is asleep, and lost in what may be a tense or disturbing dream.

If we now look closely at the young woman on the left, there is so much to explore and consider. She is the youngest person we see, by far. Is she somehow related to the other two? Are they her grandparents? She is a contrast to them in every way. She is vivacious, excited, and obviously fully aware that her picture is being taken. Her hair is stylish for the time-period, and her bathing suit is a bikini, which popularly swept the world in a fashion craze around this time. Some might judge her appearance a somewhat risqué for when the photo was taken, although the fact that she is young makes sense that she would be wearing a bikini, in comparison to the attire of her elders. Her bare shoulders lean forward, and her top looks to be hanging quite low. There is a fold of flesh along her tummy, accentuated by her lean towards the camera. The most compelling thing about her appearance though, to me eyes, is her mouth. Is she smiling at us? Is she grimacing? It seems her expression could fall somewhere between the two. Her teeth are even, but it is her gums that really grab my attention.

The image is dated in 1959, which is the first clue to a bit of deeper meaning, at least to American eyes. These were the days when the US and the Soviet Union were in full Cold War mode. The former WW2 allies were creeping further and further apart, with mutual suspicion ruling the mindset of each. While the 1950s, in the United States and most of the West, were seen as the heyday and triumph of a burgeoning youth culture, we were led to believe that the life of those living under communism in the east was subpar and stunted. Can this attitude help solve the intrigue surrounding this photograph then? We see a scene of a clear generation gap. The old ways giving way to a very different “new.” A young, stylish, bikini-clad woman, trying to express some freedom, some sexuality, while confined to the recreational world of her elders. We are peeking behind the “Iron Curtain” through the eyes of Mr. Klein. We are seeing a world, we probably misunderstood, at best, and were suspicious of, at worst. Yet, we see people no different than those probably vacationing in the shore of some American lake at the same time this photo was taken. We are more the same than we are different. Young people everywhere look to distinguish themselves from previous generations. Old folks shrug, shake their heads, when trying to understand the desires and interests of the younger generation. This is what I see when I gaze at this image.

As a footnote to this critique, I’d like to share a story. Once, in the late 1990s, while shopping in a Salvation Army thrift store on 23rd Street in New York City, I found a poster for a Klein exhibition in 1981. The poster features this same photograph. I framed it and it still hangs in my home office today, sitting right above my desk. I never tire of looking at it, and I continue to be inspired by the great work of William Klein.