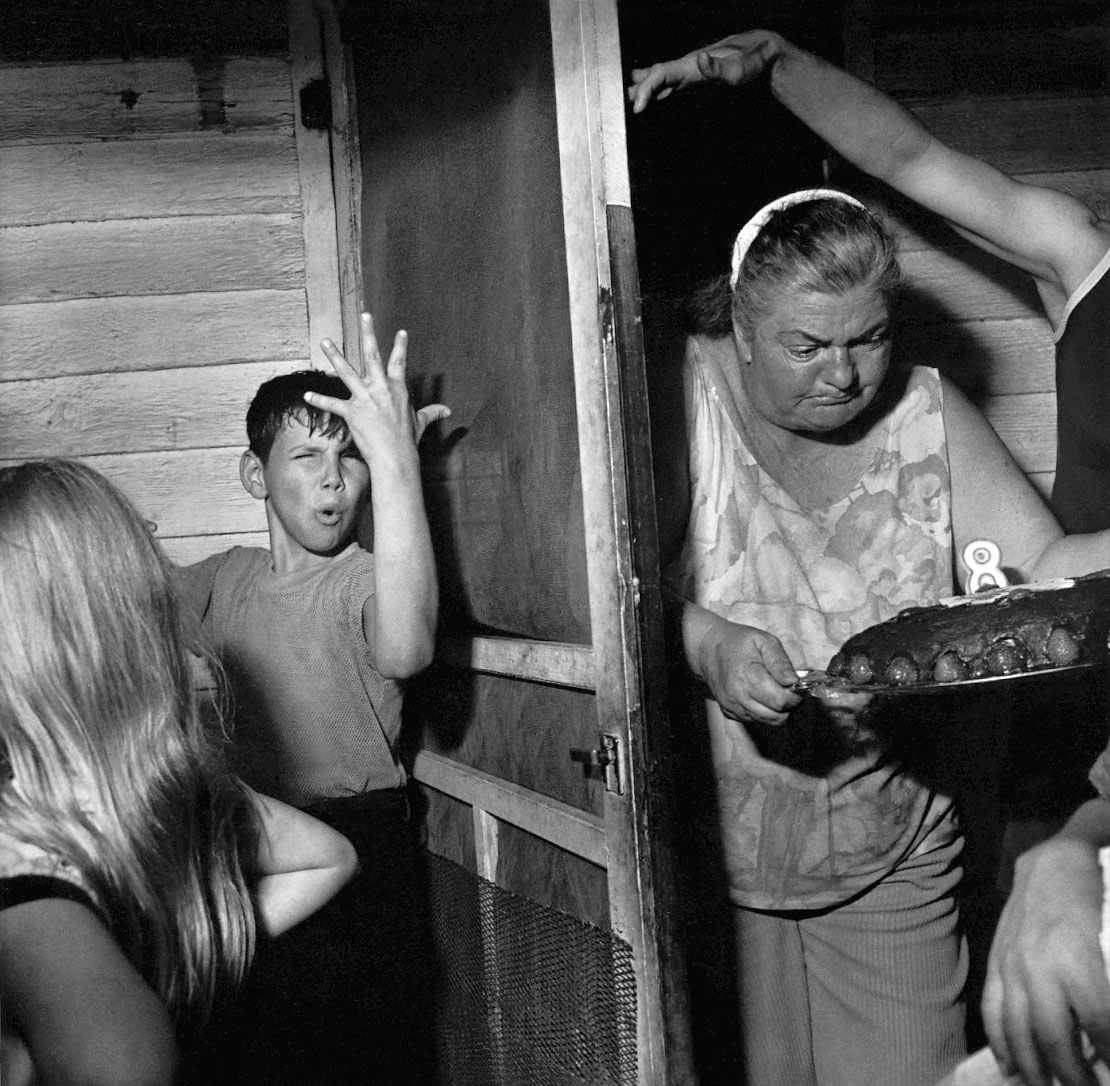

After over a year of social isolation and staying home, I have recently been feeling the pendulum swing of emotion and desire. Between the desire to get back out into the world (safely vaccinated) and the fear and anxiety of being out around people again. I think I’ve gotten used to my routine of working from home, and the prospect of being part of a large crowd… or even a small one, honestly... is filling me with trepidation. It is in that spirit that I want to take a deep exploration into this historic photograph by the enigma known as Weegee. His real name was Arthur Fellig, but as his self-aggrandizement of adding “The Famous” to his pseudonym was some indication: this was an artist with an ego. Ego was most likely part of what made him a noteworthy photographer in New York of the 1930s – 1950s. Famously shooting at night, and making the crime and violence of the “Big City” his signature subject matter, it is quite the surprise that this particular image above fits into his oeuvre at all. But not only does it fit, it encapsulates so much of New York life in general, and is a perfect vehicle to explore America society in the year before World War II.

Let’s take an overview look at this photograph. It is a summer day, obviously, and the beach is indeed packed. Claustrophobically so, in fact. Coney Island holds a near mythical place in the American mythos, and it perhaps because of this particular image that we have some idea of how it earns that standing. An escape for the masses since the early 20th century, Coney Island was the resort for the “everyman”. While the posh of the past (and present) could afford a retreat to more exclusive resorts, Coney Island was just a subway ticket token away for millions of New Yorkers. This image was created in July of 1940, and if we consider the world, the country, and the city at that time, we came see an overwhelming mass of humanity united in many ways. Also reflective of social and economic stratification that hung over America, as it crawled out of the Great Depression and slowly marched into a world war.

I find it interesting that a huge section of the crowd is actually looking at the camera. I’ve read that Weegee was shouting at the crowd and dancing to get their attention, in order to get large amounts of people to face him for the photograph. I think this adds to the power of the resulting image. You can scan the crowd and examine numerous faces, as opposed to more anonymous bodies engaged in their own personal worlds. We get to study faces, people of all shapes and sizes (but mostly shades of pale skin it should be noted.) Some eyes being shielded by the sun with hands and arms. Some behind sunglasses or the odd hat here and there. Swimsuits of all varieties. Smiles and quizzical looks. Bodies packed in the frame like sardines (a subtitle I’ve seen attached to this image in numerous places.) The crowd stretches off into the distance, completely obscuring the horizon, save for the amusement pier and rides that skirt the upper edge of the frame. The haze (I imagine it as a mix of heat, airborne sweat, pollution and ocean spray) that rides off the right upper edge of the image leads the viewer to believe that there are hundreds more people beyond what we can see.

There are many remarkable things to ponder in this photograph. Through the eyes of a 21st Century, Covid-19 viewer, I find it hard to even image such a scene existing in the present day. Any image that features a crowd of this size (such as looking at pre-pandemic concert or sporting event footage or photos) brings up a gut reaction of anxiety and fear and a general feeling of vulnerability in me. I also think about the actual times that Weegee worked in. In many ways his imagery helped define how collective consciousness accepts what New York looked and felt like back them. The visual of such a working class crowd, overcrowding the easily-accessed beach on a hot, summer afternoon bears a whiff of rose-colored nostalgia, while also making that location seem unpleasant and uninviting to an introvert such as myself. It also speaks to the state of America at that particular time. Slowly emerging from the Great Depression, but economically still hobbled, this kind of day trip getaway was the best that a working class family could hope for. Also in mind, I think about the impending world war brewing on the other side of the Atlantic. The same waters these folks are enjoying in this photo might very well be a future, final resting place for more than a few of them, just a few years later. The innocence presented (at first glance) ultimately gives way to a feeling of darkness to my eyes while I ponder the future of every person who appears within Weegee’s frame. Considering that this photo is now over 80 years old, it is safe to assume that a vast majority of the people in this crowd are now dead and gone. A day of release, of joy, of flirting, of fighting, of drinking and swimming and playing and loving and crying… gone forever but for this photograph.

Weegee went on the be most well-known for his images of crime, murder, fires and such. But what also lurked behind most of his images was the idea that was first presented by earlier photographers such as Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis. We are shown “how the other half lives.” And though Weegee generally showed these lives through a sensationalistic lenses, I still feel a sense of empathy in many of his images. This Coney Island photo is not an indictment of the folks who crowded the beach that day. If anything, it is a celebration of the dignity of the masses, those who made up (and continue to make up) the true fabric and diversity of New York City. The world shown in this 1940 photo might still feel relevant and relatable to many people who might be heading to Coney Island this summer, freed from lock down and isolation, looking for their day in the sun.

footnote: Years later, this image graced the album cover of George Michael, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1.