I live in the desert, hundreds of miles from any ocean. Sometimes, the distance is too far. Sometimes the wait to enter the wild waters of the ocean is too long. Being in water can be calming, invigorating, healing, meditative or exhilarating. Sometimes all of these things at once. I finally had the chance to return to the sea, and spend an extended amount of time enjoying the gifts that the waves and the wind and the sun can provide. Swimming in the waves at sunrise, with nary another person within sight… a gift that I cherished. I heard someone state recently that stepping into the ocean is actually stepping into wilderness. I had never considered it like this before, but it is true. An entirely different world exists out in the ocean, deep below the waves. A world of untamed life, and of unseen risks…for sure... but also one that is awe-inspiring and capable of providing unexpected transcendence. In a word: sublime.

Just a lonely guy from Jersey.

2021: 31 Hero

Who do we look up to? Who do we admire? What qualities mark someone being a “hero”? Do heroes even exist? As a child, I had a few “heroes”… the astronauts who walked on the Moon, Bobby Mercer, an outfielder for the NY Yankees; later Bruce Springsteen, then maybe Robert Frank… then…well the list kind of peters out after that.

One man who I held in high esteem since he emerged on the pop cultural scene in the early aughts was Anthony Bourdain. Bad boy chef, former junkie, writer, tv show host, traveller, citizen of the world, and sadly, lastly…suicide. Bourdain had a profound impact on my adult life, encouraging me to become a curious, open-minded (somewhat) adventurous traveller and eater. More than that, he made middle age seem cool. He was the epitome of hipster cool, in the best sense of the words.

He was also a very sad, lonely man. Looking for love, finding it and losing it numerous times. A romantic spirit forced to live in the real world. A poet, a beat, a wanderer, a punk, a cynic, an artist. I saw the recently released documentary “Roadrunner” last night (in a real theater, no less.) The film covers the rise to fame and the journey to death at his own hands. It was a story I thought I knew a lot about, but I came away with a deeper understanding of the man, his public and private life, the costs of fame and the pressures of trying to be an idealist in a less than ideal world.

Was Anthony Bourdain a hero? To me, he was simply a human being. Same as you and me. A overly curious, yet surprisingly shy man, battling demons in his own head while trying to be a force of good in the world. Inspiring, infuriating, frustrating, comical and yet, profound. A cautionary tale of the pressures of fame and success. But also a guide: to a world of possibility that exists just down the road, just around the corner, or down some dark alley in a foreign country at 2am.

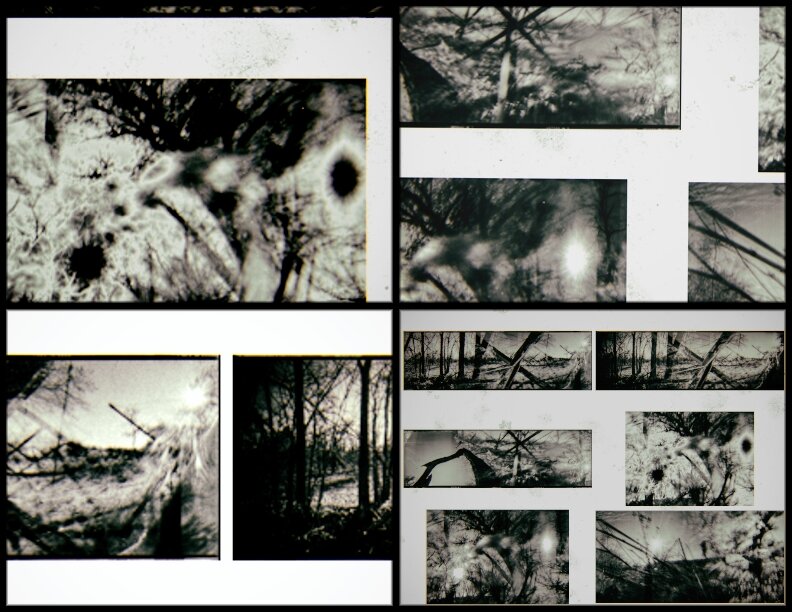

2021: 28 Lomography Film Swap

I like to tell myself that I’d never join a cult, although the matching outfits does have some appeal. The closest I’ve come to this kind groupthink is in improv, and of course, in my passion for film photography. We film heads are niche dwellers, for sure, and there is a particular sect that I’ve grown extra fond of, the good folks who populate the world of Lomography. I’ve been posting my film-based work on my “LomoHome” for quite some time now, and I genuinely appreciate the audience there. In fact, it’s much more than an audience, it really feels like a community.

A few months ago I answered a call for Lomographers interested in taking part in a film swap. The idea is that one person shoots a roll of film, then sends it on to another person to run the same roll through their camera. After processing, magical, serendipitous double exposures are revealed. Of course, the chances of crystal clear, sensical images are next to nil. Instead, the overlapping images create their own unique look. And when you compound this randomness with the fact that the images are from two very different locations…well, that’s when wonders appear.

I was sent a roll of black and white film with a fellow Lomographer from Germany. Their location was a nice foil for the urban desert shots of my southwest US environs. I am pleasantly surprised by the number of “winners” we achieved on this shared roll. But even more satisfying was the opportunity to collaborate with a another like-minded film shooter, especially since our shared roll is part of a larger group of over fifty film shooters.

Enjoy the gallery below and keep an eye out for more to come.

film still from a public domain movie, courtesy of the Prelinger Archive

2021: 27 Public Domain

When we create a photograph, a painting, a story, a piece of music… who owns the work? I don’t mean actual possession. Nor do I mean the results of a financial investment, an exchange of currency. The work, the idea, the visual stimuli, the idea, the memory? Who owns these things? The person who created it? The audience that views it? The person who purchase it? The universe that provided the material for the artist to craft? All of us? None of us?

The idea of “public domain” can be stringently applied to any work that no longer carries a trademark or a copyright. But in a broader sense, isn’t anything we artist create in the public domain? I of course wish to draw some benefit from the work I create. A purchase is nice, a comment from a reader or viewer, also nice. But what value do I draw from the anonymous consumption of my work? Is it some karmic bank account that is growing in value, like a cosmic IRA? And do I create for any reward at all? Certainly my internal thoughts, my ideas, my ego, they all benefit from my practice. And maybe that’s all I need to worry about. I make images, I type words, I speak and joke and sing, and that is all in the public domain, before evaporating into the ether.

2021:26 Pleasing to the Eye

Woke up this morning thinking about what is the root of sensory pleasure. What makes something pleasing? Why are some songs immediately danceable, hummable, everything just sounding “right”? Each sense has it’s own barometer of pleasure. And as much as we like to think we are all individuals, with individual tastes… there are many commonalities when it comes to sensory pleasure. Sweet is still sweet to most everyone’s plate. A balanced range of tones is soothing to the ear. Food relies as much on our sense of smell and sight as well as the obvious, taste.

There is, however, appeal to be found in discordant sounds, clashing flavors, scents meant to repulse or repel, and sights that confound the eyes, and by extension, the brain. I apply these thoughts to my own visual work, of course. I’ve pursued a path over the past year or so to disregard the “pleasing” image, the perfect exposure, the balanced composition. There are many reasons why, of course, often discussed here, and in my therapist’s office. But this morning, in particular, I am thinking deeply about what makes an image “good.” What makes something pleasant to look at. And why we as humans gravitate towards that. I think our brains are wired to respond more positively to something balanced, symmetrical, colored in a balanced contrast, balanced in taste, or sound, or scent, or appearance. Yet, perhaps it’s a element of contemporary life, certainly from a 21 century perspective, that with this desire for pleasure, we are ignoring the discordant, the chaotic, the “ugly” or the imbalanced.

A walk through history yields many examples of a counter to the idea of beauty, of perfection, of harmony. I tend to believe that ignoring the ugliness of the world is to deny our truly nature. And the nature of the world. I think about Werner Herzog’s musings on the subject:

“Taking a close look at what is around us, there is some sort of a harmony. It is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder. And we in comparison to the articulate vileness and baseness and obscenity of all this jungle, we in comparison to that enormous articulation, we only sound and look like badly pronounced and half-finished sentences out of a stupid suburban novel, a cheap novel. And we have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication, overwhelming growth, and overwhelming lack of order. Even the stars up here in the sky look like a mess. There is no harmony in the universe. We have to get acquainted to this idea that there is no harmony as we have conceived it. But when I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it, I love it, I love it very much, but I love it against my better judgment.”

Regarding visual art, there are myriad examples of art that has been dismissed as ugly, or in a simpler way, misunderstood when compared to the prevailing trends of its time. The history of art, all the way back to prehistoric times, is littered by modes of expression that confuse or outright offend our inner sense of beauty. Yet these works are as valuable as any “masterpiece” hanging in a museum. At the very least, they provide perspective to our definition of beauty, harmony, balance…pleasure. And any denial of darkness, metaphoric or literal, is ultimately providing the viewer, the brain, our soul… an incomplete picture.

2021: 25 Hold Still, Keep Going

Emerging from the pandemic lockdown has been an interesting challenge. Finding balance between the slow, quiet (albeit fearful) days of 2020, compared to the now open, now traveling, now meeting and working face to face reality… it’s definitely caused me some consternation. I don’t want to lose what I gained, but I also don’t want to live in a shell, away from the world. Case in point, I flew on an airplane last week to the east coast. I attended a large family gathering. I drank and ate and laughed and cried…with other people. I also spent a day in NYC, riding the subway (!), hanging out in Washington Square Park (!), eating a pastry in my favorite Italian bakery (!), and then jumping on another flight back to New Mexico. A few months ago this would have seemed impossible. Yet, here I am. I realize how privileged I am to write these words, to have experienced everything I have just described. Also, how lucky I am just to be alive, to have survived, not only the past year and a half, but also the decades before. I have turned inwards so much, it was good to step outside and feel the world around me once again. I hope for the same for all of you, whether it’s next week or next year. We are here, now. We may hold still for a moment (or months or years) but ultimately, we keep going.

Worth A Thousand Words: Ansel Adams

Preface: For those of you who followed my “Worth a Thousand Words” series, you know I usually focus on one specific photograph by a photographer and then take a deeper dive, exploring not only what the image shows but also what the photographer may have been trying to tell us, or have us think about. But for this installment, I’m going to try things a little differently and talk about one photographer and his work (and reputation) in a more general sense. Warning: some of my words may be perceived as inflammatory or disrespectful or antagonistic, all of which may indeed be true.

The God of sharpness, perfect exposure, cable releases and beard grooming

Photo credit: J. Malcolm Greany, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Today, I’d like to discuss the work of Ansel Adams. He is most likely the most well-known photographer in the history of the genre. He is held in high regard by many people, photographers and non-photographers alike. His work can be seen in many formats: not just impeccably printed photographs framed on a museum wall but also in books, calendars, postcards, coffee mugs, refrigerator magnets… I could go on, but I’ll stop there. My motivations for discussing Ansel Adams is rooted in a paradox in my own mind regarding his importance to the art form and his position in the canon of the fine art photography.

I won’t go too deeply into his biography, you can head over to Wikipedia for that. Instead, here’s a list of his achievements. I’ll mark the ones I have a problem with using my newly patented star system.

One * means… a-ok or not so bad.

The more ****s, the more something bugs me.

Ansel Adams was an American photographer and environmentalist, known for his black-and-white images of the American West. *

He was a life-long advocate for environmental conservation *

He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980. (from Jimmy Carter, so that’s cool.) *

Adams was a key advisor in establishing the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, an important step in securing photography's legitimacy. *

He helped found the photography magazine Aperture. *

He co-founded the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona. *

He helped found Group f/64, an association of photographers advocating "pure" photography which favored sharp focus and the use of the full tonal range of a photograph.**************

He developed the Zone System ************ a method of achieving a desired final print through a deeply technical understanding of how tonal range is recorded and developed during exposure, negative development, and printing. ******************* (the bane of my college darkroom education!) **********************

I have always felt conflicted when I think about the work of Ansel Adams. As a little shutterbug, I was in awe of his photos. From a technical standpoint, they seemed an untouchable level of perfection. His subject matter, predominantly his nature landscapes, showed a world (that in hindsight I realize) mesmerized my young eyes with their rendering of the sublime. However, as I went off to art school, I began to realize that the photographic medium encompassed so much more than the world that Adams was showing us. That is when I steered away from the “Ansel Adams Admiration Society.” Of course, some of my attitude was no doubt fueled by the ever-expanding rebellious streak that my college years had fostered and encouraged. I distinctly remember the first time I laid eyes on a Robert Frank photograph and needed much time and thought to reconcile that these two men were working in the same medium, yet their photographs seem so different. Frank’s (and many others’) work appeared far more visceral, energetic and also critical of society. It expanded my perception of what photography could be. And though there is still a place in the world for Ansel Adams, I moved further and further away in my appreciation for his work.

I recently stumbled upon a quote by Thomas Barrow, pulled from an interview that he did with photographer David Ondrik. Barrow’s statement about the work of Ansel Adams really struck a chord with me, finally articulating what I’ve thought about his work.

“Nobody seems to want to be challenged in photography. Maybe it is simply too easy, people want a simple rendition of what they saw at one time or another. A friend wrote, regarding the recent Adams Polaroid auction, to say he just doesn’t get it, that Adams is the greatest 19th century photographer who happened to work in the 20th. Now, Adams was a great guy, great Naturalist, Environmentalist, Martini drinker. But there’s nothing 20th century about his photography. Looking at his photos you wouldn’t know that Impressionism, Futurism, Abstract Expressionism – that there were major changes in the visual arts in the 20th century.”

What really ring true for me really for the first time and thinking about Ansel Adams was Barrow’s point about Ansel Adams being a great 19th century photographer. And looking at his work again after reading this quote I do realize that Adams seem to create his work devoid of any reference to what was going on certainly in the art world also in the photographic world and to some extent what was going on in the real world at the time that he was making his work. The lone photographer out in the wilderness lugging his 4 x 5 camera and tripod on his shoulder is it romantic vision and I wonder if that version or version of a photographer still even exist today. With a Instagram and iPhones everyone’s a photographer of course, and I’m not going to beat that dead horse any further. The dedication to the craft that Ansel Adams exemplified should still garner respect. However, I think that the medium has moved so far beyond what Adams was showing us in his photos, the majesty of nature the pristine landscapes the almost mythical views that he shared with us. I think you could possibly make photos like that still today but my question is: why would you do it? That’s not to say that all art and in general and photography specifically needs to deal with the harsh realities of human life on this dying planets however Adams work in my mind belongs even more so on a postcard or a calendar. Because ultimately those images sure world that in my mind is nothing but a fantasy. One that would be better served by a painter with oils and canvas. The technical achievements that Adams showed throughout his life end up looking like nothing but pretty pictures to my jaded, 21st Century eyes. I’ve heard enough photographers wax poetic about “Moonrise Over Hernandez, New Mexico.” Take a ride through that area today and that “fantastic scene” of a full moon over a sleepy high desert town…well it just feels like about as far from reality as you can get. And trust me, if I hear the origin story of that image one more time, with the legendary “no light meter” hook, I think I’ll drink a warm mug of D-76.

Still, I would be remiss if I did not give some credit to Mr. Adams. He certainly elevated public and collector’s attention towards fine art photography. He also, in some ways, liberated photographers who followed him. No longer did we need to pursue the epic location, the sublime vista, the perfect composition, the sharply focused negative, the full tonal range print. My own reckless abandon… taking sharp blades and flames to my negatives, surely has old Ansel spinning in his grave.

One steaming mug of D-76, please!

I certainly don’t mean to take a hammer and chisel to the feet of a monumental photographer, but at the same time this exploration has given me the opportunity to reassess where Ansel Adams work and reputation belongs. With tongue firmly planted in my cheek, I’ll just say that I won’t be spending any of my cash on an Ansel Adams calendar or coffee mug anytime soon.

2021: 21 A Complete Meltdown

Shooting film sets its own limitations on the photographer. You don’t work with a “raw” file… a pristine, neutral “capture.” A digital file ready and waiting for its pixels to pushed and pulled in countless directions. Film has boundaries inherent in its manufacture. Light sensitivity in particular, but also more simple restrictions, such as “black and white” or “color.” I recently picked up a couple of rolls from the great folks at Lomography. All were color film, and the one that I was most looking forward to playing with was their Lomochrome Purple offering. Color shifting is inherent in this particular film, with greens shifting to purple, and reds and blues being accentuated in an unpredictable manner. I decided to expose the film on my recent sojourn to the deserts of Arizona. I figured the flora and fauna of springtime would be an excellent opportunity to test the boundaries of this film.

Upon development (at my local film lab) I scanned the resulting negatives. I must be honest, I wasn’t initially pleased with the results. Maybe I just don’t like the color purple (sorry, Prince) but I was underwhelmed by the images, save for a few photos that had more going on from a compositional standpoint. Working in color is always a stretch for me, but this particular exercise was beyond what I would consider a success. I scanned the film, posted a few of my favorites online, and put my negative binder back on the shelf.

…and then this week I took another look at the negatives. This time, I decided that a drastic revisit was in order. In a move now familiar to a few friends (and the handful of readers to this blog) I released my toolkit of scissors, tape, bleach, sandpaper and heat gun onto the unsuspecting strips of film. My dulled Xacto blade was surely striking a dagger into the ghost of Ansel Adams. I’ve been obsessed with Julian Schnabel lately, and the time in my studio, with the scent of burning plastic mixing with the warming New Mexico spring air, was driving me to channel his heroic attitude towards image making to the extreme. I approached the film with reckless abandon, not giving a f*ck about the results. The process of destruction being the act of creation was all that mattered.

As for the results, I am much happier now. Bleach and heat transformed the Lomo-color-shift into another realm. Is it good? Debatable. Is it art? Probably. Is it satisfying? Definitely.

sic transit gloria imago

“Crowd at Coney Island, July 1940” © Weegee; image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Worth A Thousand Words: Weegee

After over a year of social isolation and staying home, I have recently been feeling the pendulum swing of emotion and desire. Between the desire to get back out into the world (safely vaccinated) and the fear and anxiety of being out around people again. I think I’ve gotten used to my routine of working from home, and the prospect of being part of a large crowd… or even a small one, honestly... is filling me with trepidation. It is in that spirit that I want to take a deep exploration into this historic photograph by the enigma known as Weegee. His real name was Arthur Fellig, but as his self-aggrandizement of adding “The Famous” to his pseudonym was some indication: this was an artist with an ego. Ego was most likely part of what made him a noteworthy photographer in New York of the 1930s – 1950s. Famously shooting at night, and making the crime and violence of the “Big City” his signature subject matter, it is quite the surprise that this particular image above fits into his oeuvre at all. But not only does it fit, it encapsulates so much of New York life in general, and is a perfect vehicle to explore America society in the year before World War II.

Let’s take an overview look at this photograph. It is a summer day, obviously, and the beach is indeed packed. Claustrophobically so, in fact. Coney Island holds a near mythical place in the American mythos, and it perhaps because of this particular image that we have some idea of how it earns that standing. An escape for the masses since the early 20th century, Coney Island was the resort for the “everyman”. While the posh of the past (and present) could afford a retreat to more exclusive resorts, Coney Island was just a subway ticket token away for millions of New Yorkers. This image was created in July of 1940, and if we consider the world, the country, and the city at that time, we came see an overwhelming mass of humanity united in many ways. Also reflective of social and economic stratification that hung over America, as it crawled out of the Great Depression and slowly marched into a world war.

I find it interesting that a huge section of the crowd is actually looking at the camera. I’ve read that Weegee was shouting at the crowd and dancing to get their attention, in order to get large amounts of people to face him for the photograph. I think this adds to the power of the resulting image. You can scan the crowd and examine numerous faces, as opposed to more anonymous bodies engaged in their own personal worlds. We get to study faces, people of all shapes and sizes (but mostly shades of pale skin it should be noted.) Some eyes being shielded by the sun with hands and arms. Some behind sunglasses or the odd hat here and there. Swimsuits of all varieties. Smiles and quizzical looks. Bodies packed in the frame like sardines (a subtitle I’ve seen attached to this image in numerous places.) The crowd stretches off into the distance, completely obscuring the horizon, save for the amusement pier and rides that skirt the upper edge of the frame. The haze (I imagine it as a mix of heat, airborne sweat, pollution and ocean spray) that rides off the right upper edge of the image leads the viewer to believe that there are hundreds more people beyond what we can see.

There are many remarkable things to ponder in this photograph. Through the eyes of a 21st Century, Covid-19 viewer, I find it hard to even image such a scene existing in the present day. Any image that features a crowd of this size (such as looking at pre-pandemic concert or sporting event footage or photos) brings up a gut reaction of anxiety and fear and a general feeling of vulnerability in me. I also think about the actual times that Weegee worked in. In many ways his imagery helped define how collective consciousness accepts what New York looked and felt like back them. The visual of such a working class crowd, overcrowding the easily-accessed beach on a hot, summer afternoon bears a whiff of rose-colored nostalgia, while also making that location seem unpleasant and uninviting to an introvert such as myself. It also speaks to the state of America at that particular time. Slowly emerging from the Great Depression, but economically still hobbled, this kind of day trip getaway was the best that a working class family could hope for. Also in mind, I think about the impending world war brewing on the other side of the Atlantic. The same waters these folks are enjoying in this photo might very well be a future, final resting place for more than a few of them, just a few years later. The innocence presented (at first glance) ultimately gives way to a feeling of darkness to my eyes while I ponder the future of every person who appears within Weegee’s frame. Considering that this photo is now over 80 years old, it is safe to assume that a vast majority of the people in this crowd are now dead and gone. A day of release, of joy, of flirting, of fighting, of drinking and swimming and playing and loving and crying… gone forever but for this photograph.

Weegee went on the be most well-known for his images of crime, murder, fires and such. But what also lurked behind most of his images was the idea that was first presented by earlier photographers such as Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis. We are shown “how the other half lives.” And though Weegee generally showed these lives through a sensationalistic lenses, I still feel a sense of empathy in many of his images. This Coney Island photo is not an indictment of the folks who crowded the beach that day. If anything, it is a celebration of the dignity of the masses, those who made up (and continue to make up) the true fabric and diversity of New York City. The world shown in this 1940 photo might still feel relevant and relatable to many people who might be heading to Coney Island this summer, freed from lock down and isolation, looking for their day in the sun.

footnote: Years later, this image graced the album cover of George Michael, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1.

2021:19 Batting Practice

Practice makes perfect. This is a statement that at its foundation, is based on a lie. There is no perfection, at least when it comes to human pursuits. Try as we might, we never quite reach perfection. Sometimes we miss the bull’s-eye by a fraction of an inch, sometimes we missed the target completely. Yet, we strive. We reach for the golden ring, even though it is ultimately just out of touch.

I’ve been thinking about the idea of practice quite a bit lately. This blog is part of the weekly practice of mine. Recently I started a daily writing practice, which I begin every day with. Filling one small page with whatever is on the top of my head at that particular moment. I find it helps to have the ritual, regardless of the results. Making art, shooting photographs, performing improv, these all demand constant practice. With constant practice, comes nearly constant struggle, constant frustration, constant shortcomings. Sometimes things end up feeling like a complete failure. But even these moments are critical, and end up being valuable.

Another adage is that we learn from our mistakes. And this might not always be true, but if we’re lucky, we do sometimes learn lessons from our mistakes. That’s why practice is so critical. Especially when it’s a daily practice.Because sometimes, the right thought… the right word… the right photograph… presents itself through this practice. But more often than not, I am faced with what I call a “near miss.” And sometimes a complete swing and a miss.

Which brings to mind the idea of batting practice. This is a reference to baseball, but I’m sure it applies to other sports, and other pursuits in general. If we think about the best hitters in the history of baseball, their batting average is somewhere between .300 and .400. This basically means that even the greatest players did not get a hit six or seven times out of every 10 times they stepped up to the plate. And these are the best of the best. You could be a professional baseball player and maybe bat around .250 and be considered a pretty good player. Meaning you’re only getting on base one out of every four times at bat. For us mere mortals, our batting average, I’m sure, is even lower. And you can apply this to any pursuit; professional, amateur, hobby, art.

As you know I shoot a lot of film. I know it’s been said generally that if you have one winning frame per roll of film, one keeper, you’re doing pretty well as a photographer. One out of 36 frames. That’s not a very good batting average. Now think about the luxury of shooting digital, and having no real limit on the number of pictures you can take. The ability to delete immediately the photos that you consider failures. I think it’s really important, to keep the bad pictures, to keep the failures. To fight against your low batting average. To scrape and struggle and work hard to try to improve your batting average, a few percentage points at a time. Some games you may strike out every time you step up to the plate. Sometimes you may hit a home run. But every time at the plate is part of playing the game.

As a footnote to this post, I find it ironic that my first attempt at writing this entry was a complete failure on my part. I inadvertently forgot to save my first draft as I was typing, and lost everything I had written. A swing and a miss.